Walking to St George’s – Charles Holden.

Walking to St Georges – Charles Holden

This is the third and last of our trilogy centred on those weeks of walking to and from St George’s Hospital in the latter part of 2019.

Why Charles Holden? Well there is a pub named after him opposite Colliers Wood Underground Station.

The Charles Holden pub at Colliers Wood.

But who was Charles Holden?

For a detailed biography you might like to read this Wikipedia article.

But, for the purpose of our story, we are confining ourselves to the period in which he became most famous for his involvement in what would become London Transport. In particular, the London Underground, and then the section of the Northern Line that passes close to St George’s Hospital.

Brought up in North Cheam, Surrey. Bobby was very familiar with the Northern Line from Morden to Central London. His first job was in the City. Taking a 93 bus to Morden and the tube to the Bank station. Suitably dressed in Hush Puppies. Half mast trousers. Too short a sports jacket. A pipe and an umbrella. The word “twot” comes to mind, but weren’t we all once. He soon lost the umbrella and saved the pipe for when he met his girlfriend at Morden Station. There they crossed the road to the Odeon cinema opposite. She had brought dinner in Tupperware boxes. After which he lit his pipe with clouds of smoke to the consternation no doubt of all those close by, but then they were all smoking as well. Each pair of seats had an ashtray screwed to the back a few inches from the people in front. Chewing gum stuck to your shoes and yet lustful youngsters all headed for the back row for a few hours snogging. There was nowhere else in the warm – apart from the upstairs back seat of a 93 bus.

The Technical Director must interject here. He is a great fan of traditional cinema. He remembers the Odeon (Gaumont, as it was then) in Bournemouth. A Super Cinema, at that time divided just into two – the former balcony as one screen, the stalls the other. Sitting in the stalls, one could imagine it in its heyday. Naturally, he has looked up the history of the Morden cinema, located just opposite the Underground Station on the junction of London Road and Aberconway Road.

Designed by architects J. Stanley Beard & A. D. Clare, it was built by for a Herbert Alfred Yapp for his Forum brand in the Wyanbee Cinema Circuit, but opened as the Morden Cinema on 7 December 1932. It had a Compton 3 Manual/8 Rank organ, and was the first Compton organ to be fitted with an illuminated console. It seated 1,638 In common with many other Super Cinemas of the day, it also had the capability for live performances, with a small stage equipped with two dressing rooms and a café for patrons. There was also a 300 space car park. Just three years later it was sold to the Odeon chain, taking on that name, finally closing, still as a single screen cinema, on 13 January 1973. It became a B&Q store, still largely untouched. Sadly, it was demolished in 1990 after B&Q moved out. An Iceland store now stands in its place.

Halcyon days in 1962.

Morden Underground Station.

Odeon Morden.

Auditorium of Morden’s Odeon. 1,638 could be entertained here.

Cinema ashtrays.

It was to be 57 years before walking to St George’s, an inquisitive bear and writing stories revealed a fascinating history of the Underground between Morden and Clapham South Station. And, of course, Charles Holden.

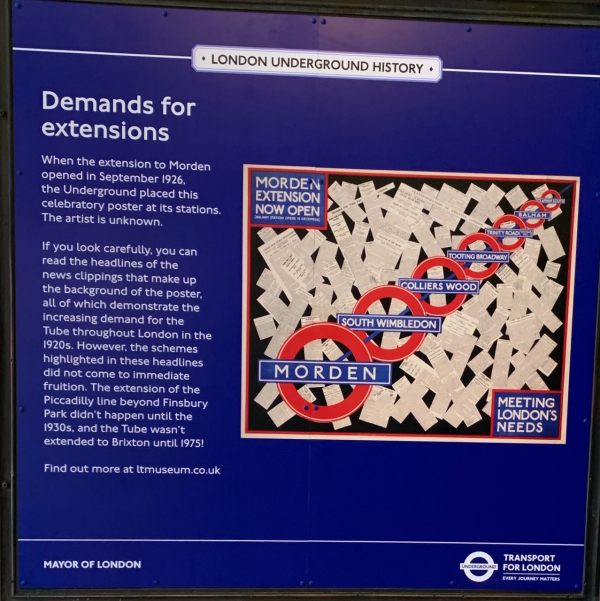

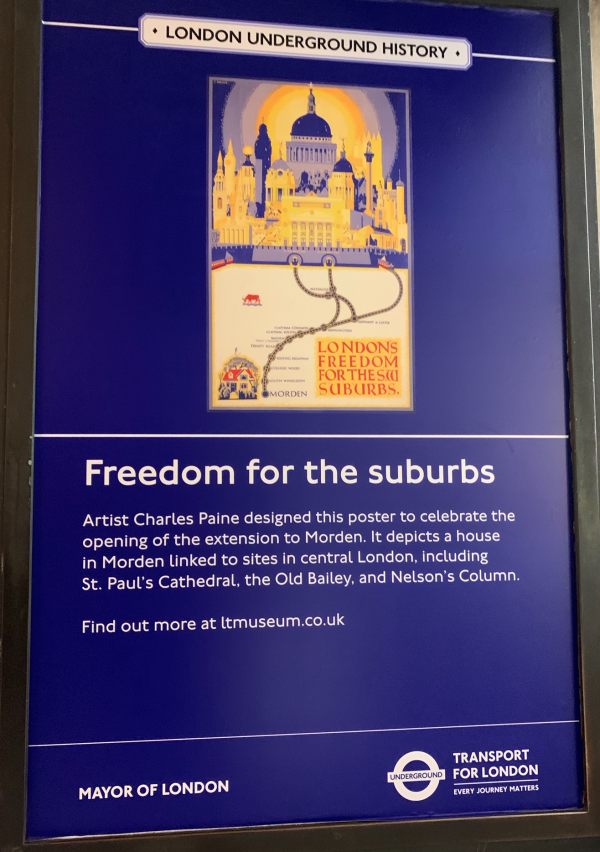

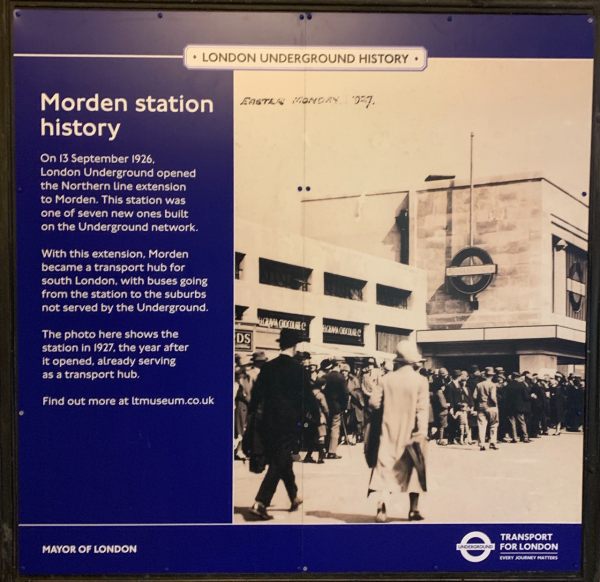

The story is divided into stations. Seven in all. In 1924, the then City and South London Railway was to be extended south from Clapham Common to Morden. Still the most southerly station on the entire Underground network. Frank Pick, General Manager of the Underground, chose Charles Holden as architect to design all seven stations. Once you start looking, you can see the similarity between each one and, as we visit all seven, we can pick out features that have remained unnoticed since Bobby’s young days. The exteriors all reflect a simple modernist style that Charles Holden had used in France designing war cemeteries.

Morden.

Morden Station. The original facade now nearly 100 years old. Classic Holden features of a glass screen with the roundel central between Portland stone pillars Two more roundels (one hidden) on flag poles. The office block a later addition.

Morden Underground Station in early days.

Morden has distinctive Charles Holden features but, being the terminus, is much bigger than the others. The trains are also above ground as they enter the station from the tunnels. Tunnels which were once regarded as “the longest tunnel in the world”. At 17.3 miles, when the trains emerged into the daylight at East Finchley. Morden could easily be a separate story, but here are some facts.

The Underground was originally intended to reach Sutton. But the first World War and competition from the main railway at Sutton prevented it going beyond Morden. The plan was to extend the District line from Wimbledon to Sutton. The land was purchased and fenced. The main line railway objected, as they thought it would provide a faster route to London. Years later it did become the main line through Wimbledon Chase and various stations including West Sutton to Sutton itself.

One odd fact was that at North Cheam, then in Surrey, London Transport had their sports fields near the current Sainsburys. The reason being that the land had been purchased for the failed railway line.

Most importantly, it is really important to note that Morden terminus was built in the middle of a field. The proposed lines all went across virgin territory. Sutton itself was already a ‘railway town’ from the time the mainline reached it in Victorian times. Cheam was a village. In general, everything in between was countryside. The coming of the Underground to Morden sparked an enormous building boom that led to the biggest council estate in Europe. Together with Bobby’s own Brock’s Drive and the Park Farm Estate. It’s hard to imagine. But then, it was nearly one hundred years ago.

Morden Station.

South Wimbledon.

Here you see the distinctive Charles Holden exterior simplicity. Like the next five stations, built on the corner of a road junction. The glass screen with the roundel between stone pillars. Two more roundels set on flag poles either side of the entrance. Inside, the stations still have their original features. All with similarities. At South Wimbledon, we feature the escalators (no lifts).

The escalators themselves have clearly been modernised. But the uplighters? The plasterwork looks original. (The picture actually shows the stairs between the escalators).

Art Deco… ish.

Distinctive original tiling and bench.

The platform has a sharp curve, negotiated with squealing wheels, where the line turns 90 degrees towards Morden.

Colliers Wood.

Colliers Wood Underground Station. Spot the common features? Not just me…

Colliers Wood escalators.

One feature throughout all the stations is what Bobby described as ‘pleasant decrepitude’. They are all in a shocking state and have a desperate need for some TLC. They are all so busy, could that ever be achieved? And yet they have an air of ‘old’ about them that he quite likes.

Pleasant decrepitude.

Pleasant decrepitude again.

Colliers Wood.

Tooting Broadway.

Spot the Holden features!

The station for St George’s Hospital. Here we feature the entrance hall. As for all of them. Double Height, clad in Portland stone. With an ornate skylight. The Underground roundel framed in a glass screen. Divided by stone columns.

The double height entrance hall with a glass skylight.

Tooting Broadway escalator.

Pleasant decrepitude at Tooting Broadway.

Tooting Bec.

There are those features again…

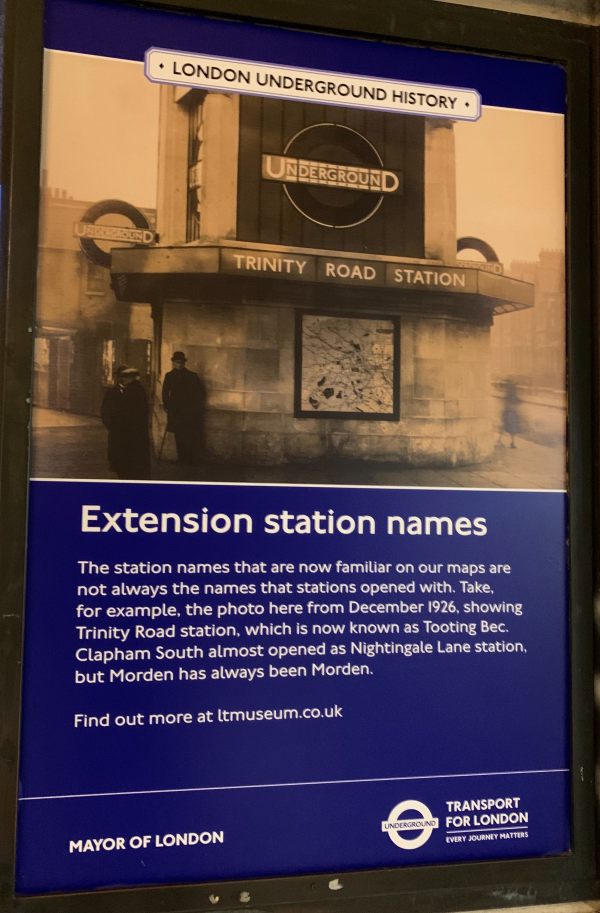

Tooting Bec was originally known as Trinity Road.

It has two entrances. The far one serving as a subway to the main station. Once again, an entrance hall with a glass panel ceiling.

Second entrance for Tooting Bec, serving as a subway to the main station but still incorporating Charles Holden features.

Tooting Bec was once Trinity Road station. (Named after the A214 which becomes Trinity Road instead of Tooting Bec Road at the junction with the A24).

There’s the roundel within the glass screen between stone pillars. Here again is the distinctive tiling. We really liked Tooting Bec that has still got the original mahogany handrails.

Nice handrail. I wonder how many hands have grabbed that in 94 years?

Pleasant decrepitude? Original tiling.

Tiling… Bench?

Balham.

Charles Holden again.

Curved stairs at Balham, but still those wonderful handrails.

Balham handrail.

Glass screen, roundel, stone pillars, tiling, handrail, skylight out of picture. Over 14 million people access this station annually. A station that hasn’t changed that much visually for nearly 100 years. It is a living museum.

Balham escalators (stairs).

Balham also has two entrances.

Here we feature the distinctive green and white tiling. The simple wooden seats.

Clapham South.

Classic Charles Holden features. The first station on the extension.

Was once proposed to be Nightingale Lane. See white direction board.

Another double height entrance, glass screen stone pillars.

Escalators, stairs, tiles and uplighters at Clapham South.

Skylight at Clapham South.

Tiles, bench.

And finally.

Clapham South is one of eight London Underground stations with a deep level air raid shelter underneath it. In 1948, the deep shelter was used as temporary accommodation for immigrants from the West Indies. The HMT Empire Windrush arrived at Tilbury in 1948, carrying 492 immigrants. London had a severe labour shortage after the war and the Colonial Office had sought to recruit a labour force from Jamaica. An advertisement had appeared in Jamaica’s Daily Gleaner on 13 April 1948, offering transport to the UK. The Windrush was quickly filled. As there was no accommodation for all of the new arrivals, the Colonial Office housed many of them temporarily in the deep-level shelter at Clapham South. The underground shelter opened its doors to the public in 2016. The London Transport Museum offer tours of the shelter. Quite expensive, but always over subscribed.

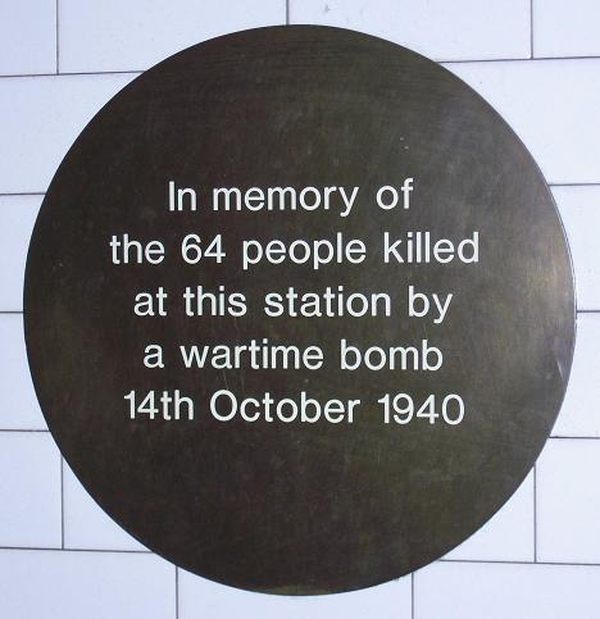

Balham was one of many deep tube stations designated for use as a civilian air raid shelter. At 20:02 on 14 October 1940, a 1,400 kg semi-armour piercing fragmentation bomb fell on the road above the northern end of the platform tunnels, creating a large crater into which a bus then crashed. The northbound platform tunnel partially collapsed and was filled with earth and water from the fractured water mains and sewers above, which also flowed through the cross-passages into the southbound platform tunnel, with the flooding and debris reaching to within 100 yards (91 m) of Clapham South. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), sixty-six people in the station were killed – although some sources report 64 shelterers and 4 railway staff were killed and more than seventy injured. The damage at track level closed the line to traffic between Tooting Bec and Clapham Common, but was quickly repaired, with the closed section and station being reopened on 12 January 1941.

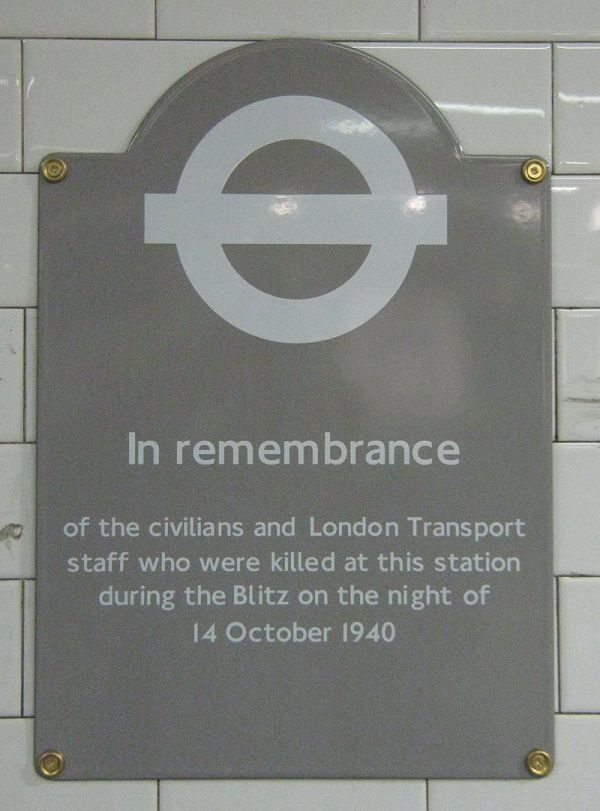

In October 2000, a memorial plaque commemorating this event was placed in the station’s ticket hall. It stated that 64 lives were lost, which differed from the CWGC register at the time, and other sources. On 14 October 2010 this was replaced with a new commemorative plaque, which does not state the number of fatalities. This second plaque was again replaced with an official memorial stone in Welsh slate commissioned by London Underground and that was unveiled on 14 October 2016. The second removed plaque was again deposited with the London Transport Museum.

The original plaque.

The second memorial plaque in the entrance hall, now replaced.

The memorial plaque unveiled on 16 October 2016.

The bombing of the station during the war is briefly mentioned in Ian MacEwan’ novel ‘Atonement’, while the film based on the book depicts the station’s flooding, where a main character is killed. Both the novel and the film date the event incorrectly, with the novel placing it in September 1940, and the film dating it as 15 October rather than the previous day. The film also refers to the fracturing of gas mains, as well as water. The bombing of the station is also featured in the children’s novel Billy’s Blitz by Barbara Mitchelhill, when Billy and his family are sheltering in the tube station on the night of 14 October 1940.

Morden

The population of the parish of Morden, previously the most rural of the areas through which the extension passed, increased from 1,355 in 1921 to 12,618 in 1931 and 35,417 in 1951.

Lighting a Candle for Diddley

The illuminated sign is the best seller at The London Transport Museum. Comes with eight different names, including ‘Mind the Gap’. Bobby loves it, but thinks it unlikely that Diddley would have done. She was creative, artistic and obsessed with white and ivory colours. Bobby brought a lot of colour into her life. She brought a lot of colourful life into his… and he misses her. We all do.

Fascinating stuff Bob. But then again I like the tube!Thanks for a really good Mindfully Bertie and Happy birthday!

You make .London come alive for me. Thanks

Fasinating stuff, really good photo, well done Bobby, I understand there were 13 platforms redesigned (tile designs) in the extention by Charles Holden; Balham, Clapham South, Colliers Wood, Elephant & Castle, Kennington, Oval, South Wimbledon, Tooting Bec, Tooting Broadway, Charing Cross, North End (maybe, although never finished), St. James’s Park and London Bridge. Do you know of any others?

Hi Mike – What a shame. Bobby would have loved to have caught up with you on all this. Sadly, his untimely passing means that this can’t happen. But thank you so much for your comment. Tim.